Tommy Fleetwood finally won. Now comes the hard part

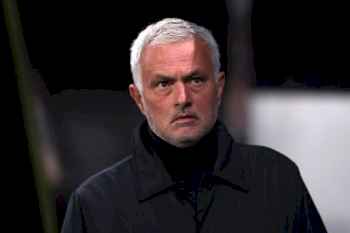

On the final Sunday evening of Tommy Fleetwood’s 2025 season, the reigning FedEx Cup Champion finally relaxes. The mid-November sun has set in his adopted hometown of Dubai, making it just chilly enough for a sweatshirt as Tommy, his wife and manager, Clare, and a few local friends slowly drain a bottle of wine in his backyard. He’s learned over the years that any libation after golf gets him a bit, he says, “loopy,” but for the first time in a long time Fleetwood is enjoying an exhale.

It’s so nice not to care how I’ll feel in the morning, he thinks to himself.

Predictably, just a few hours later, he wakes with a grape-induced headache, remembering that, for him at least, Mondays are mandatory. So, he gets in his blue-and-gold, Ryder Cup-styled cart and drives across Jumeirah Golf Estates to the teaching academy that bears his name.

“I have this thing,” he begins, a bit sheepishly, “where I feel some guys won’t practice on Monday after an event. But if I do, I feel like I’m getting better.”

That morning session is just the start. On what should be the first off day of a much-needed offseason, Fleetwood spends five hours on the 17th tee at JGE’s Earth Course, expertly regaling each giddy foursome that comes through. Every 10 minutes he launches the same 170-yard missile, poses for pics and yells “Golf shot!” whenever an approach lands safely on the island green. With those piercing blue eyes and that Lancashire accent, the just-turned-35-year-old is an easy charmer.

Between groups, he plops down on a nearby bench for chats about everything from Santa Claus to tai chi to the dragonflies in his garden. (He’ll bend your ear on all three.) At some point the topic of these mandatory Mondays comes up, and you feel the restlessness of his golf life. Fleetwood has just finished the finest season of his career, playing golf at a level so high — wins on both the DP World Tour and the PGA Tour, a starring role at the Bethpage Ryder Cup — he just wants it all to slow down.

“I cannot believe that the season is over and it’s Christmas,” he says. “And that freaks me out. Where is it going? Time freaks me out a bit.”

WHETHER IT’S FELLOW PROS, family or just another golf writer, everyone has been asking him the same thing lately: What’s different, mate?

“It’s an obvious question to ask,” Fleetwood admits when we regroup a day later. “Surely there must be something different. I ask myself that all the time as well.”

To be a golf fan in the summer of 2025 meant asking the question too — and wondering if “Fairway Jesus” was actually capable of manifesting miracles. In his 15-year professional career, Fleetwood had won all over the world but was 0-for-163 in bagging a win at the game’s top tier: the PGA Tour. Twelve times he’d finished top three, zero times he’d lifted the trophy.

Can I close tournaments? he’d ask himself after those near misses. Why haven’t I done it? Do I have what it takes?

PGA Tour event No. 159 — the 2025 Travelers Championship — was particularly agonizing. On the 72nd hole, he made a sloppy bogey not just to surrender his lead but to miss out on a playoff too. Seven weeks later, in early August at the FedEx St. Jude, he was alone in the lead with three holes left. Every other contender played those holes in two under. Fleetwood went one over, missing another playoff by a stroke.

The rep he was earning “was impossible to ignore,” he says. Doubts crept in during the tensest moments, an affliction that never plagues the player in 40th place. But rather than coalesce into some unbeatable boogeyman, the close calls somehow reduced Fleetwood’s fear of falling short — so long as he forced himself through a sick form of therapy. When it would have been natural to retreat and discreetly lick his wounds, he went straight to the media and rewired his perception of those negative experiences.

“If you’re gonna take the highs, you have to take the hits as well,” he says now. “I’m talking to myself when I’m doing those interviews. I knew that if I spoke straight away and said the right things — the things I wanna hear as well — that it was a really important part of the process for me.”

Fleetwood’s fearless vulnerability struck such a chord with PGA Tour staffers that, at their annual orientation for rookie players in November, they used his post-Travelers presser as a peak example of media relations. If some of Fleetwood’s maxims — “Thoughts and feelings are the most natural things we have; you can’t fight them” — seem straight out of a self-help manual, they very well might be. He works with sports psychologist Bob Rotella and rereads his books often.

This commitment to mindfulness is partly why, just two weeks after the St. Jude collapse, LeBron James and Caitlin Clark tuned in as Tommy forced his way into contention on Sunday at the Tour Championship at East Lake. The public response to his eventual triumph that day was predictably seismic. Fleetwood may have beaten just 29 players, but his years-long journey to a PGA Tour win cracked some mysterious popularity code that the Tour’s execs have been studying ever since. Rafael Nadal and Michael Phelps sent congratulatory messages. Posting on X, Tiger Woods wrote: “No one deserves it more.”

“[It was] f–king amazing,” says Fleetwood’s putting coach Phil Kenyon, who watched nervously that Sunday from a hotel room in the Bahamas.

“I never had any doubt in Tommy’s capabilities. You just don’t want it to build up into something that it isn’t, so it was more relief [than anything else], just for him to get the monkey off his back.”

Ultimately, Fleetwood’s breakthrough was as foreseeable as that wine headache in Dubai, and it uncorked a level of play he’s never displayed before. In September 2025, he led all Ryder Cuppers in Strokes Gained, going 4 and 1 for triumphant Team Europe. Three weeks later, he won the DP World India Championship. Each successive achievement sparked the same question: What’s different, mate?

The truth: Tommy still doesn’t know.

He wants to believe his recent form — and his ascent to career-high World No. 3 — is just how he plays golf now. He swears he made the same on-course decisions all summer, both in victory and defeat, proving to himself (and plenty of golf statisticians) that results are random but consistency is key. Kenyon likens it to Kaizen philosophy, a Japanese business concept of slow, incremental — even unnoticeable — gains that build to something greater.

A little fire never hurt, either. In Dubai, at the DP World Championship in November, Fleetwood’s Ryder Cup teammate, Rory McIlroy, spent 10 silent seconds pondering the idea of What’s different about Tommy?

“I would never say that Tommy questioned how much he wanted it,” McIlroy began. “But he’s always been so nice. So nice. And then I’m like, Is he too nice? Because you need to have just that little bit of edge or prick in you — whatever you want to call it. I know I have it, and I feel like that’s what you need to win. I think it’s harder for Tommy to feel that because of how empathetic he is. But this year, I feel like he’s developed that little bit of edge.”

Talk to people around Fleetwood and it’s clear that McIlroy isn’t the only one who thinks so. Fleetwood, on the other hand, needs a minute to process it. “Yeah,” he says, shrugging his shoulders. “But I’d like to think nice guys can win too.”

IF FLEETWOOD’S GOLF CAREER looks like a vector inching upward, his golf life is more elliptical, somehow always returning to the intersection of Selworthy and Granville roads.

When he was 17 and growing up in Southport, a town of 94,000 on England’s west coast, he raced over to Selworthy and Granville, fresh off earning his driver’s license. That’s where the nicest houses in town were, closest to the Irish Sea, each of them a modernist break from the redbrick norm. He’d slow down to make the hard-right turns, dreaming about which plot he’d buy when his golf got so good that he could afford it.

His more famously devious visits to Selworthy and Granville started when Tommy was 8. On special occasions, he and his dad, Pete, used the intersection to sneak onto Royal Birkdale, the private club in town. They’d walk the muddy footpath, veer off into the trees, eventually stumbling onto the 5th tee of the course that will host this year’s Open Championship.

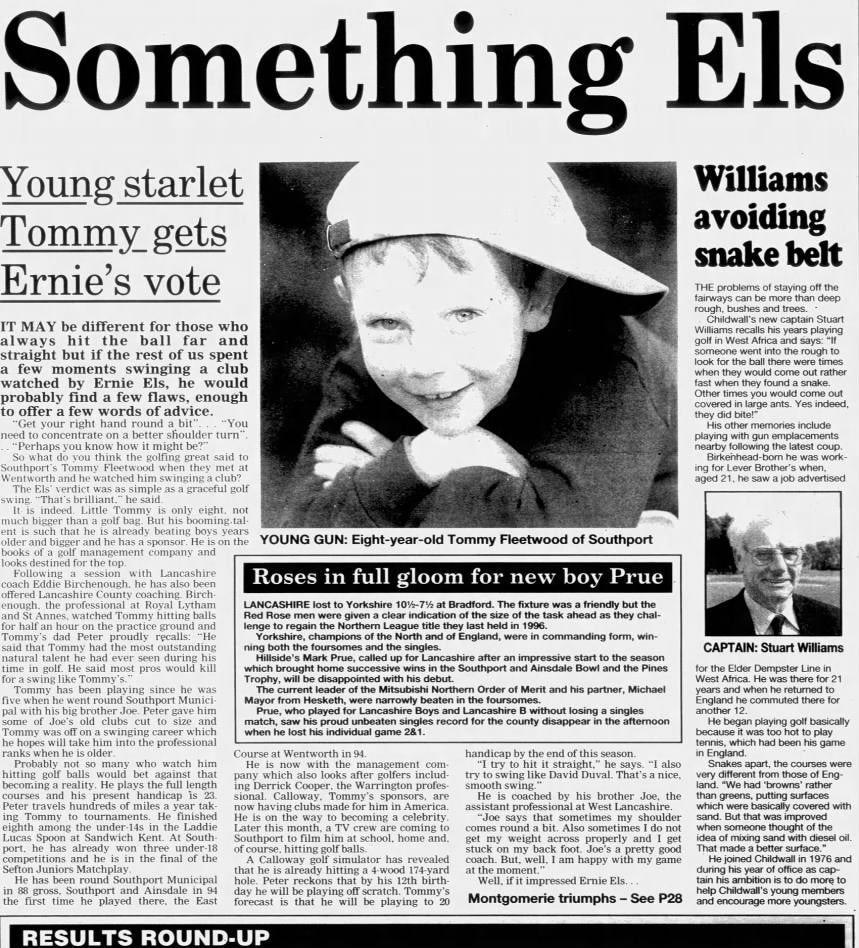

The Fleetwoods lived more modest lives than those of the Birkdale membership. His mother, Sue, was a hairdresser; Pete worked in construction. They raised two sons in a tiny home. Pete introduced them to golf at the local muni, where 16-and-unders played for free. He sawed down full-size clubs to junior length, and it’s a good thing he did. By age 6, Tommy’s golfing brilliance was already gracing the local sports pages.

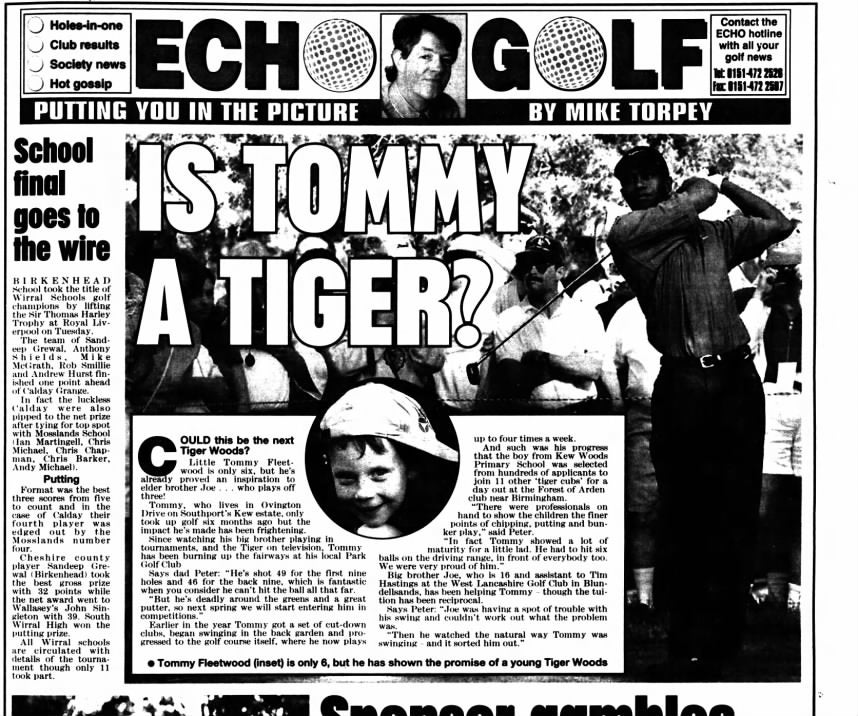

He was only a year into primary school when the papers dubbed him the Southport Starlet and dared to ask: Could this be the next Tiger Woods? Tommy was a mainstay in those pages throughout his adolescence, pictured hitting balls at a youth clinic with Lee Janzen, always flashing that toothy grin under a backward TaylorMade hat.

“He was exceptionally gifted,” Kenyon says, “but he practiced a lot. Whenever I went down to hit balls at Formby [Hall]— which was a lot, because I was a golf geek — he’d always be there.”

“He hit it farther, higher, more consistently than anyone else,” remembers Jim Payne, who worked with Fleetwood from his junior days to the launch of his pro career. “You couldn’t compare him at his age with another junior because, really, there wasn’t one. You were comparing him with somebody three years older.”

Alan Thompson, likely the most impactful swing whisperer of Fleetwood’s career, called it intimidating. “You could see he was great. When you’d speak to him, he’d fix you with this gaze. I can distinctly remember thinking, What’s this lad thinking here?”

All his coaches mention that intentionality, which clearly hasn’t been lost over the years. For the majority of that 17th-tee hang at JGE in Dubai, Tommy’s phone is 20 feet away, face down on the table. He prefers small-group affairs but can’t help asking questions of strangers rather than shoo them away. Like any elite pro, he shakes hundreds of hands every day, but he seems to understand the value of giving a piece of himself to anyone who asks: the struggling, 23-handicapper; the freelance photographer; even the two teens who, on a nearby road, screeched their dad’s SUV to a halt so they could bound onto the tee and beg for an autograph.

Fleetwood makes it easy to agree with McIlroy. So nice — the degree to which will be tested more than ever in July when the Starlet returns home, and to Royal Birkdale, along with 155 of the best golfers in the world. “It’s probably my biggest dream in the game — to win that tournament,” he says.

A visit to Southport reminds you that it takes a village. Fleetwood was given free rein as a youngster at the local Formby Hall facility, where he won club championships back then and now has a lounge and academy named after him. The majority of his coaches hail from the greater Liverpool area. In 2016, during what he calls “the worst year of my career,” Fleetwood made one panicked call and sent one frantic text from the Shenzhen International in China. The former went to his dad, who still calls Southport home, and the latter to swing coach Alan Thompson (better known as Thommo), who three years earlier had stopped working with Fleetwood. Thommo jumped into action, organizing a team sit-down and full reset for when Tommy returned to the UK. It took months, but by the end of that year they got it right. Part of the reshuffle was a new caddie, Ian Finnis, who has known Fleetwood since he was a boy and has now carried his clubs for a decade. Finnis lives just 12 miles south of Birkdale. During the Open, he’ll probably commute by train.

It was at Birkdale in 1998 that 7-year-old Tommy first attended an Open and first saw Tiger Woods in the flesh. In 2017, when Fleetwood played in the Open at Birkdale, his face was plastered on lampposts across town. His grade school alma mater, Scarisbrook Hall, pulled hundreds of kids into the schoolyard to hold up a Tommy Fleetwood banner for a good luck video. The locals holed up at The Golden Monkey, around where Pete Fleetwood still enjoys the occasional pint — they remember what Tommy wore and where he sat the last time he came through.

With that pride comes a bit of longing and lust. For all that England’s Golf Coast offers, with some of the best courses in the world, it has struggled to produce a player with real staying power. Now they’ve got one and are eager to make the most of it. Amanda Cooke, who manages the pro shop at Southport Golf Links, where Tommy first started playing, just wants him to visit for five minutes and a photo. The image of him beaming at the local muni would do wonders for it and their shoestring budget. “Tommy Fleetwoods are like hen’s teeth,” Cooke says. “They don’t come around more than once every hundred years.”

Six months ahead of the Open, it all begs two questions, one answer unknowable and the other absolutely certain: Will Fleetwood’s greatest-ever form still be here when he needs it most? And how will Southport handle it if it is?

“You’re definitely not old enough to remember this, but you might have seen footage,” says Norman Marshall, Tommy’s first coach and the head pro at the local Fleetwood Academy. “It’ll be like when the Beatles first landed in America. That’s what it’s gonna be like.”

Marshall’s being cheeky, but you can tell he believes it. And he’s not alone. Alan Thompson agrees. “It’ll be absolutely mayhem.”

Phil Kenyon makes it a hat trick: “It’ll be mental.”

ABOUT 3,500 MILES FROM SOUTHPORT (and about 60 degrees warmer) is Discovery Downtown, a 23rd-floor, open-air rooftop club in Dubai — the epitome of affluence and the site of our cover story shoot. A swanky extension of Discovery Dunes — the first private golf course in Dubai — it stands close enough to the tallest building in the world, the Burj Khalifa, that the skyscraper’s luminous reflection of the morning sun serves as secondary lighting for the photography crew and stadium lighting for an impromptu game of Ping-Pong.

After sitting for 45 minutes of grooming, Fleetwood slips into a dark Loro Piana suit, causing his pristine smile to pop even more. In between camera flashes, he’s distracted by the sight — hundreds of feet below and at least a thousand yards away — of a new TAG Heuer retail shop. He’s a brand ambassador.

The morning checks every box for how different life can look when pro golf takes over: the sky-high photo shoot, the Italian designer threads, the watch sponsorship, all in taxfree Dubai, which is attracting more pros every year. But for at least a week now — since the DP World Tour Championship that closed out Fleetwood’s thrilling 2025 campaign — a press conference question from the event has been top of mind: What would that kid from Southport think of his career?

“That little boy from Southport, there’s still loads of things he dreamed of that I, the older Tommy, haven’t been able to achieve,” Fleetwood said at the time. “But I’ll keep striving for that.”

He didn’t bother to share specifics in such a public setting, but he finds power in stating his dreams plainly, if only to himself.

“It should never change even when you get older,” he says, “but when you’re young, dreams can go as far as you want, and that’s how it should be.”

He’ll jot them down on paper, big or small, and even meditate on them, visualizing each vivid detail. It worked for him in October, when his 8-year-old son, Frankie, guilt-tripped his dad about timing his wins better. Tommy had never won with Frankie in attendance, meaning Frankie had never known the thrill of running onto the green for a victory hug. A week later in India, Fleetwood committed the idea to paper, then visualized it throughout Sunday’s back nine. He won by two and Frankie got his hug, one final reminder that in a golf year dominated by Scottie Scheffler and remembered for McIlroy’s indelible Masters win, we may have learned the most — about life, at least — from Tommy Fleetwood.

During our shoot, he shares thoughts that feel like a window into his golfing soul. Like how the favorite token of his career is the silver medal he won at the 2024 Olympics in Paris. Or why he’s pursuing moments — or simply more Frankie hugs on the 18th green — far more than trophies. And why he wants to bring a Tommy Fleetwood Academy to numerous countries in Asia. We talk about how he maybe hasn’t appreciated everything he’s done because, well, there’s always something else to achieve. Mondays are mandatory.

Our chitchat is so persistent that at one point the photographer barks: “Okay, now look at me this time. And no talking!”

The silence lasts only minutes before we’re onto a timely Tour debate. Would you rather have had Scottie Scheffler’s 2024 season—nine wins, one major — or Xander Schauffele’s: two wins, both of them majors, one of them the Open Championship, the oldest tournament in the world?

“If I won two majors and one was the Open at Birkdale,” Fleetwood says, pausing, then exhaling at the thought. “Maybe I would just ride off into the sunset.”

The photographer’s flash hits him again. Maybe, just maybe, that Monday would be optional.

This story was first published in the January-February 2026 issue of GOLF Magazine. The author can be reached at sean.zak@golf.com.

The post Tommy Fleetwood finally won. Now comes the hard part appeared first on Golf.