Old Tom's Well was never so quaint as its name suggested. I reflected on this fact as I fell into its depths, which had so far refused to provide the full stop of death.

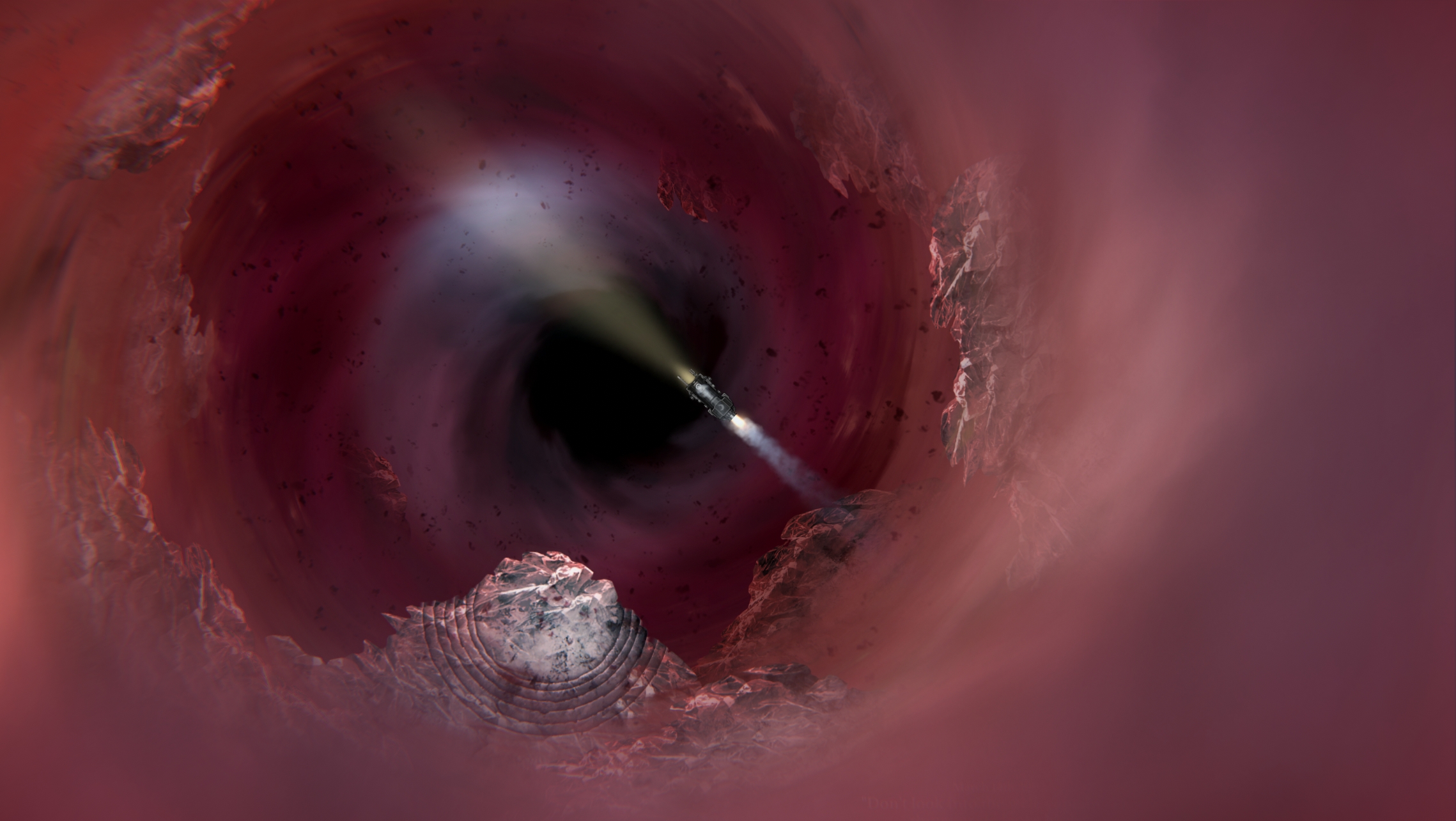

A spiralling green vortex, the well had long been a terrifying blot of ink in the story of my journey across Sunless Skies. The very sight of it filled the crew of my locomotive with terror, and getting close meant grappling with winds that threatened to dash the ship against icy asteroids—the only land in the vicinity of this great lidless plughole.

If that was the well, what did that make Old Tom? I knew the legends, of course: a desperate prospector had travelled the Reach in the earliest days of London's ascension to space, looking for his fortune. The story goes that he made a wish at the well, and later struck a lucky vein in the Mother of Mountains, funding an extravagant retirement overnight. Broken people came ever after, hoping to repeat the trick—clinging to the periphery of a howling hellhole that offered no solace, their bitterness hardening into a cultish form of self-pity.

I knew—should have known—that this isn't the kind of well where you make wishes. Only deals. But there were plenty of warnings I hadn't heeded. I'd been oh-so-careful as I navigated the skies across dozens of hours, eyeing my fuel reserves and darting between the sonar blasts of swooping, smothering bats, their tattered black wings so wide they threatened to block out the clockwork sun. I'd started to tell myself that this captain, the one I'd created, was the only one I'd ever need—completing every quest in spite of the permadeath, the constant threat that loomed larger than the bats. I'd become blind to the danger that grew aboard my own ship, sleeping and working and gambling alongside the crew.

When I first met Tom, he was called something else. The Amiable Vagabond was his name—not particularly strange in the context of Sunless Skies, where most NPCs bear a similarly colourful adjective-noun identifier. What stood out was his joviality, which made him a more attractive hire than the Fatalistic Signalman. The skies are stuffed with horror and darkness, and any light is a godsend—particularly when it doesn't appear to be permeable, persisting no matter the awfulness of your circumstances. The Vagabond puffed a pipe between the hairs of a bushy grey beard. He laughed a lot, and played the fiddle in a way that sent clear water coursing down the coal-stained faces of the most hardened stokers.

He said he belonged to—was the king of!—a group of travelling adventurers named the Skylarks. We flew together to Port Avon, where the Vagabond introduced me to folk like Sooty Jim and the Chimney Kid, who drank from flasks and sang of their escapades and stamped out rhythms around a campfire all through the night. Perhaps I was a Skylark? After all the crewmen and women I'd watched starve to death or drift into the abyss as their tethers snapped, it seemed comforting to file everything I'd been through into a folder marked 'adventure'.

I was only too happy to help resolve a wrong in the Skylarking community. A nomad named Quivers, gone missing. Alongside the Vagabond, I followed a trail of secret signs. Searching for answers, I broke an old bandmate of the vanished man out of prison in London, where she'd been imprisoned for "marvellous crimes". A letter suggested Quivers had been chasing an old Skylark dream of the Sugarspun Garden, an idyllic idea meant to warm travellers on cold nights.

When a stranger told me, in fearful tones, that the Vagabond was Old Tom, I confronted my friend. He accepted the charge without batting an eye, blaming his disguise on debts and enemies, not least among them his own sister. She, he explained, was a cult leader who now traded off his story, tempting vulnerable loners to the well for sacrifice. That was surely where Quivers had vanished to.

When we took a detour to the woods to conduct a ritual the Vagabond assured me was crucial to our quest, the game presented an unexpected option: to tip out the strange liquid he was insisting I drink. But I scrolled on by. After all, I trusted Tom. He sang in harmony with the birds, and his eyes twinkled. This mission was one of many in my log, and offered that which was in short supply elsewhere in the skies: a ready villain and a chance to do good. More than anything else, it was the twinkle that killed me. "Thank you for everything," he said. "This will make a fine story when it's over."

Tom's wish was, of course, a deal. Riches in return for the sacrifice of his own life at a later date. But the Vagabond, it transpired, had used his wealth to consult a host of scientists and witches, who had come up with a way to spread Tom's soul by ritual. He need only lead others to the well and, with the help of his sister, toss them in—staving off the terrible cost he'd agreed to.

Once I'd hit the well's bottom, I was dead. Dead-dead, in a fashion I hadn't ever really expected from a series of branching conversations. But as a seasoned rogue-liker, I knew what to do next: dive straight back in. Only by rolling a new captain, and rolling with the devastating punch, could I take the blow and find joy in the game again.

In some ways, Sunless Skies is a very generous roguelike. Upon death, it allows you to pass your ship, with most of its fixings, down to the next captain—alongside the resources and equipment you had in the bank, and a hefty chunk of your XP. What it doesn't pass down, however, is the progress of any unfinished quests; the innumerable stories you've invested in, the steady march towards the conclusion of your Ambition, the time you've spent with companions who aren't traitorous bastards. It was upon opening up my empty quest log that I found myself keening at my monitor, almost doubled over with the pain of loss and betrayal. This, I felt, was an outcome I could not process nor live with.

Then came the bargaining, of the sort Old Tom was familiar with: I realised there was a way out of the permadeath pact I'd made. Somehow, amid my wailing, I hadn't yet quit out of Sunless Skies. The save I had pushed to an untimely endpoint existed in a state of temporal instability, yet to be uploaded to the cloud. By booting up my Steam Deck, I could return to a time earlier that morning when Tom was still twinkly, and I was still breathing. All that remained was to trick a lifelong friend into self-doubt. "That's odd," said Steam, when I returned to my main PC. "I have a bunch of terrible memories on the local drive, but in the most recent cloud save, all is dandy. Which is true?" I clicked, carefully and soothingly, to replace the local files. There there, old chum. All is well. And what is truth, anyway?

Armed with awful knowledge, my soul stained, I returned to the woods and Tom's ritual. I switched the cups and flew the fucker to his well. The pipe fell from his mouth as I explained that the con was finished. He sobbed as the winds picked up, pulling him over the edge and into the black bowl below, leaving behind only the frostbitten fingertips he'd used to cling desperately to the ice. No captain would ever see the Amiable Vagabond again.

A few days later—perhaps a month, in-game—I travelled to the astonishingly dangerous Blue Kingdom, where the dead go to be assessed and funnelled through Death's Door. When a dreadnought cracked my ship open like a pecan, killing me instantly, I felt something complicated. But the feeling that came through most clearly was relief. Permadeath had been a gift, one that granted regular tension and strategic complexity to the entire game. It had elevated Sunless Skies, and my time with it. I had failed to hold up my end—to abide by the game's judgement of my failures—and a cost needed to be paid. As I died, I felt the unease finally lift. I thought back to the words of Tom's sister, as she peered over the lip of the well after him: "It is done."